Board Working

Before jumping into the woodworking, I’d like to address something that has been on my mind lately.

I appreciate you joining me here to read about my life in the workshop. It’s no secret that life outside the workshop is incredibly tumultuous and troubling these days. One thing I hold most dear about my workshop and craft, is that they serve as a refuge and gathering point for people to come together and share an interest. I believe meeting this way and spending time together, especially while learning, is healthy and positive. Our day to day communication has largely been overtaken by online and mass media discourse. I’ve retreated from contributing to social media because it strikes me like a blender full of gravel. Adding another rock to the mix by joining in doesn’t seem helpful or productive. Yes, I have very strong feelings about many events and topics of the day, but for the most part, I will continue focus on the the real world ways actions I can engage in that align with my own values and intentions.

I do believe it’s important to lay out one of my dearest held convictions to help inform anyone who follows me here and aspires to attend an in person workshops. I want you to understand what you can expect. In my shop, everyone is welcome and equal. We don’t talk politics or religion in the shop, because of the divisive nature of the topics. These beliefs can easily remain private, but if you aren’t comfortable with more obvious attributes, be it the color of someone’s skin, physical attributes or gender, then you should be aware that you will likely be sharing space with people different with you. I don’t just tolerate diversity, I invite and work to welcome all people in the woodworking community.

I know that to some, this will sound like I just threw a handful of stones in the blender. But I am not talking about an agenda. You see, I was introduced to woodworking by a black man. In art school, it was women and gay people who taught me to use machines. The furniture makers who befriended and inspired me when I was starting in New York were lesbians, immigrants and recovering addicts. The guitar maker who shared his shop with me where I made my first chair is black. People who are different than me have played critical roles in my life in the workshop. I am not describing an effort to impose a change, as far as I’m concerned, it’s been their space all along.

Over the years I’ve seen the variety of students expand and it’s made classes more lively and interesting for everyone. I built my workshop in hopes of creating more opportunities to learn about woodworking, each other and ourselves. I hope you will join me here and experience the joy of learning and sharing space can bring to our lives and community. Thank you again for your support and for joining me here, I truly enjoy creating these posts and am honored to have your attention.

On to the woodworking.

Recently, I made a trip to Highland Hardwoods to pick up some ash for an upcoming Temple chair class and thought I’d share some of the process of selecting and processing the material I bought. I have some very specific reasons for buying certain boards, starting with the width, thickness and relationship to the center of the tree. I don’t look for the widest boards possible. It’s best when I can get an even number of parts worth out of the width, because that means I can start by splitting the board in half. Any time wood is split in equal halves the split will more reliably follow the fibers. Beginning with splitting is a reliable way to expose any twist in the fiber line in the board (this is how I handle boards from species like ash and oak that split well). I do buy boards where I will first have to split of a third of the width, but this is only if other wider boards have flaws.

I also look for boards thicker than the parts I need because once I split the board, the growth rings revealed on the split surface act as a guide to cut material away from the thickness to make the part follow the fibers. If the board is too thin, there isn’t enough room for shifting the position of the part to align with the growth rings.

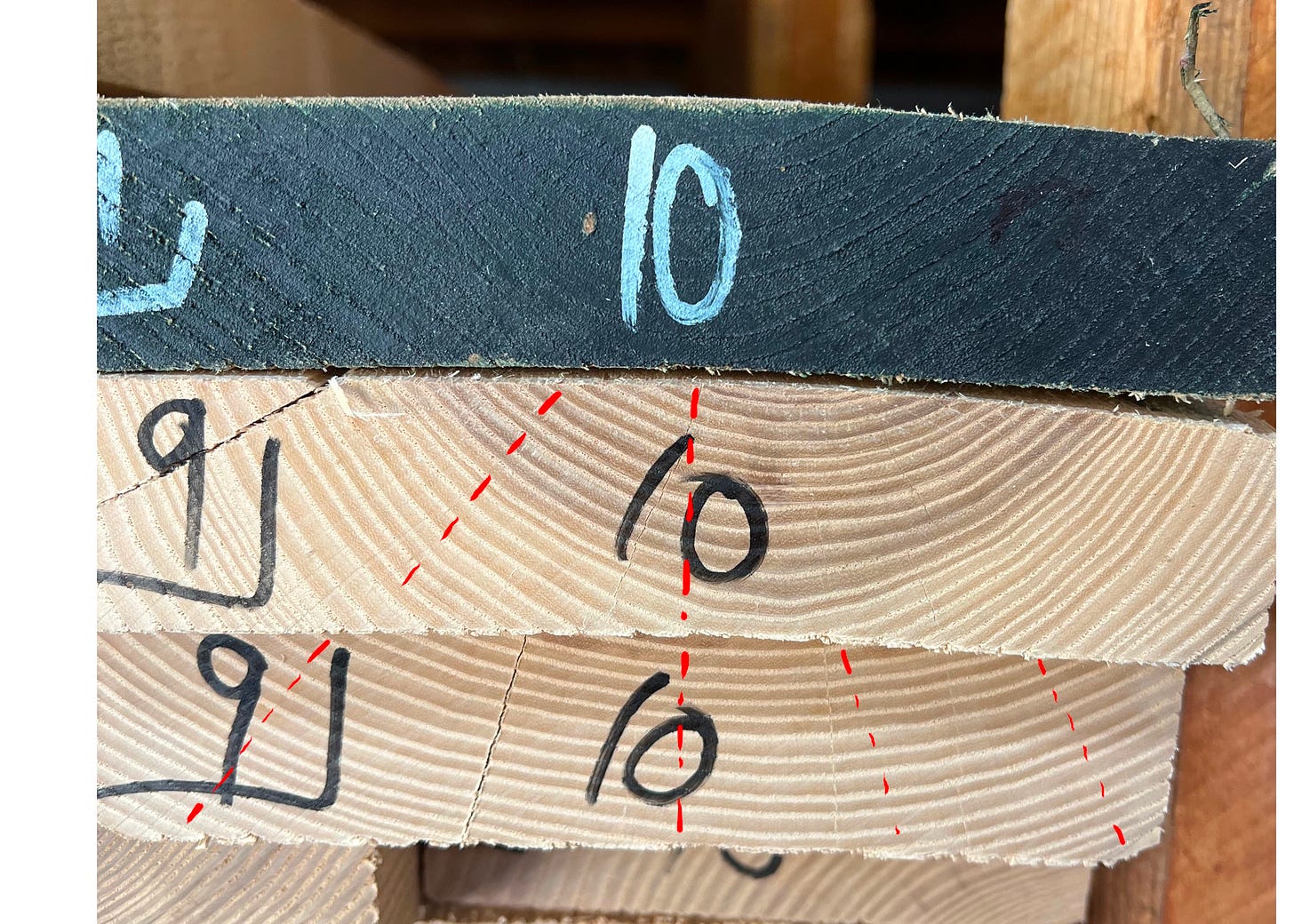

The process can be made much easier by simply selecting boards that have been sawn parallel to the growth rings. You can see where the saw cut across the growth rings on the surface of the board, which shows up a “cathedrals”. For parts such as turnings, I can usually work my way around a little misalignment between the sawn surface and the fibers, but for bent parts, I am looking for flatsawn boards (parallel to the growth rings) that have long stripes without many exposed “cathedrals” on the surface. The lower half of the board below is a good example of the saw being in line with the growth rings.

The longs cathedral at the bottom is perfect for bent parts, but the top of the board reveals that the tree wasn’t perfectly straight.

I expect that most boards taken from the tree near the base will have an area of extreme misalignment with the growth rings. I just cut this area and discard it or if the board is thick enough, I will likely be able to get smaller parts.

The middle board in the image displays this issue. It happens because of the flare of at the base of the tree and doesn’t define or affect the rest of the board.

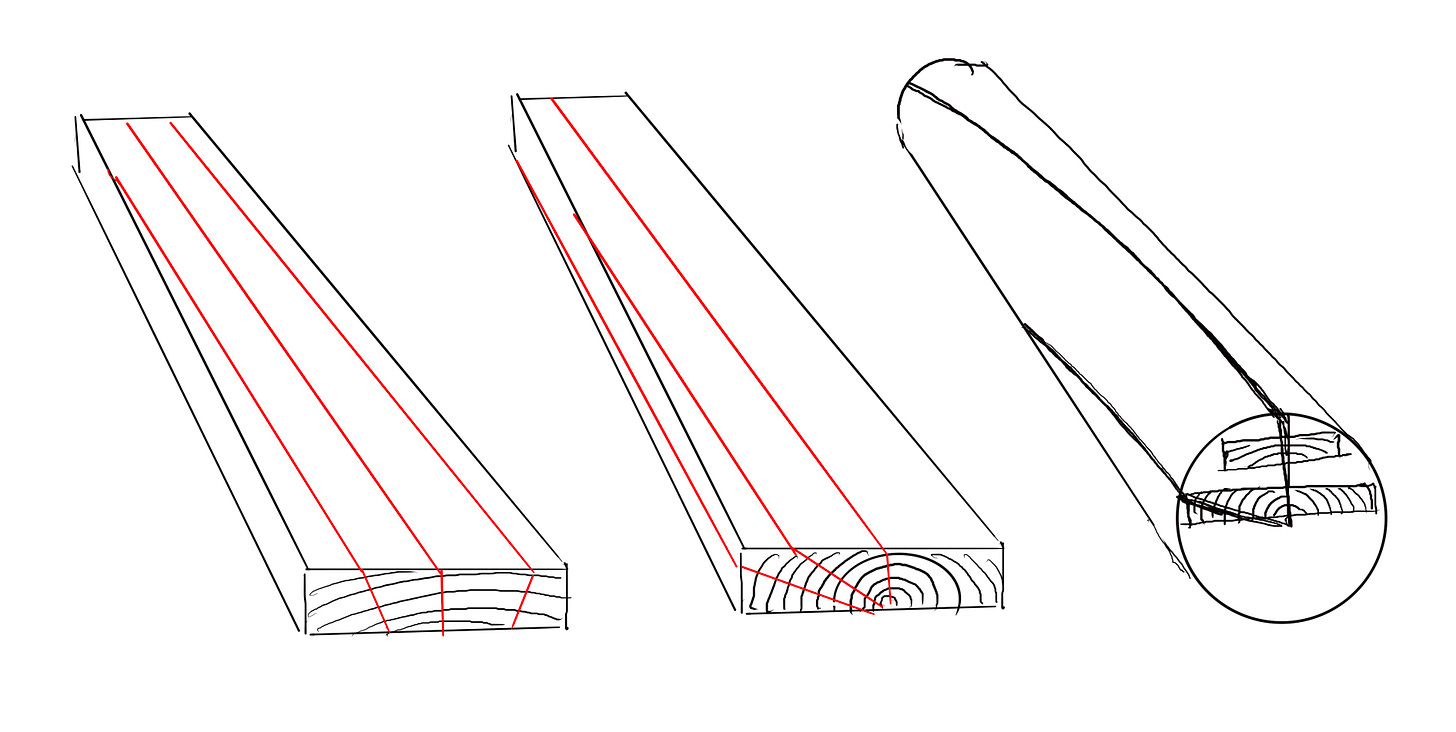

Once I assess the size and relationship of the surfaces to the growth rings, I need to consider the potential twist in the radial plane. The problem of twist in a tree travels in the radial plane (from the center of the tree to the bark). A board can have a surface perfectly in line with the growth rings but if the tree was wildly twisted, then the entire board will all be short grain. To understand this will require a little more of a deep dive. Imagine a crack in the radial plane traveling from one end of a log to the other. If it’s a twisted tree, the crack might be in the 12 o’clock position at one end of the tree and 10 o’clock at the other. You can see this in the image below on the right. When splitting a log along the radial plane, the split naturally follows the twist. But on sawn boards, I need to understand how the radial plane travels through the board to expose where the fibers travel.

One the left side of the image above, there’s a board cut far from the center of the tree. These tend to be narrower, as you see in the image on the right. The way the radial plane passes through this board is relatively uniform. Yes, the angle of the radial plane shifts a little, but because these boards are narrower to begin with, the effect is minimal. By contrast, look at the board in the middle, which was sawn near the pith of the log. The radial plane is vertical through the thickness in the middle of the board, but near the edges, it takes on an extreme angle, becoming nearly horizontal. You can see that a slight twist in the tree results in a shift along the face of the board near the center, but near the edge, the twist radial plane causes a shift along the thickness of the board. The technique of splitting the board down the middle to expose the fibers and then sawing parallel to the split doesn’t work on the board in the middle image. The radial plane shifts too much. I know it’s a bit of a brain breaker, but in practice, my rule is just to steer clear of boards near the pith.

Here is a real world example of the different angles of the radial plane in two boards sawn from different parts of the tree. Splits in the endgrain reveal the radial plane. (I’ve also added red line to show the ray plane in the rest of the board.) Look at the split in the second board down in the stack. This board, sawn near the center of the log shows the extreme angle of the ray plane near the edge. Any twist in this board will cause the ray plane to travel along the thickness of the board, making it difficult to get parts thick enough to use. Yes, the center of the board can be split and reliably used, but near the edge, the center split can not be used as a reference for sawing. By contrast, the third board down was sawn far from the center and the angle of the ray plane won’t shift nearly as, making it more reliable to cut all the parts parallel to the middle split to get parts across the full width of the board.

The other deciding factors are common to selecting logs. I look for fast growth trees, which are stronger and tend to bend better. Remember, if the growth rings are large, then the shift of just a few rings might mean the board is sawn quite a bit off from parallel to the fibers.

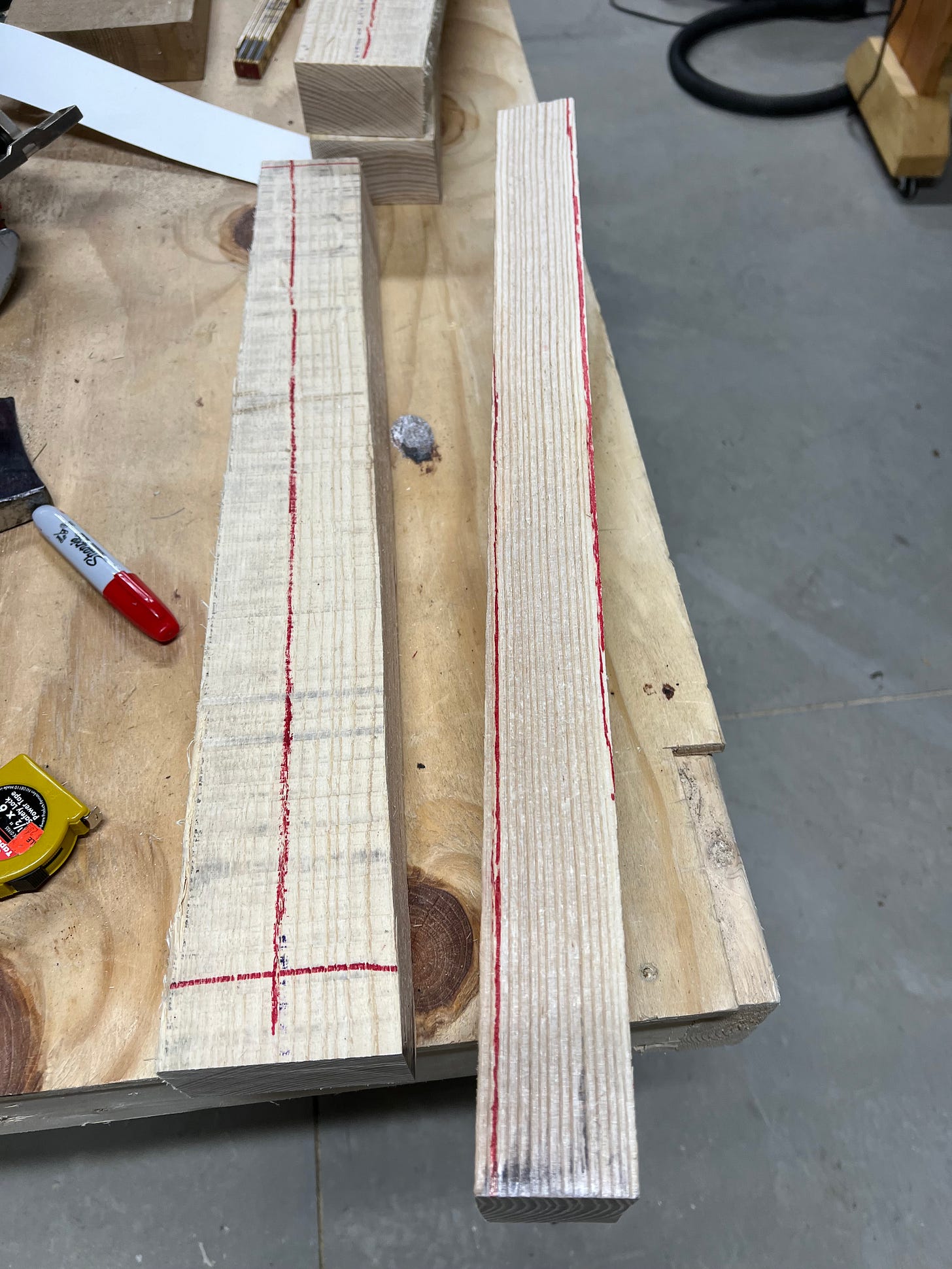

Below is one of the boards I bought as I split it down the center.

Afte splitting it, I drew lines parallel to the split to define the parts. In this case, I’ll get three legs and a smaller area on left will become stretchers or arm posts.

Next, I saw out along the lines and then rotate the parts to examine the angle of the the growth rings on thickness. In the image below, I’ve drawn on the part on the right where I will saw the part to align the growth rings with the surface of the part.

It worked beautifully and I was able to turn all my legs as though they were split from the log. Not only are they stronger, but the turned surface is better because I can always get clean cuts on the entire surface when cutting from thick areas towards thin areas. Here is one of the legs on the lathe. The growth ring running uninterruped down the length of an evenly size piece is a telltale sign of successfully aligining the part with the fibers.

My relationship to woodworking changed irrevocably when I started working wood that aligned with the fibers. If you want to use and enjoy hand tools, I highly recommend using split wood, or at least learning to “find” the split wood in a board.

Finally, I’m considering hosting a “Best Photo of Georgia” contest. Here is my latest entry.

Aspen took this one last week. Similar pose but big points for the workshop composition.

.

Send yours to peter@petergalbert.com and I’ll post them for a reader’s vote!

An excellent post. Thanks for helping popularize the use of kiln dried wood in Windsor chair making. Its a great alternative for us hobbiests who don't have ready access to suitable, green logs. Following your writings/videos I was able to rive all the parts for a contiuous arm settee from hickory, oak, ash and hard maple. I followed your suggestion to use ash for the steam bending and after soaking, it bent beautifully. And now, when I go to the lumberyard, all those grain lines in a board begin to mean something to me. Many Thanks.

A helpful post indeed. Your description of the desired natural structures visible in a potential board isn’t stated so clearly anywhere else that I have seen.

And, your initial comments are most welcome too in the present relational climate. To merely say, “ We don’t discuss politics or religion “, just presents two more negative statements and they fall to develop a positive environment of understanding and acceptance as you have done so effectively. Well said.