I spend a lot of time thinking about curves, both by themselves and in relation to the overall design of a chair. Don’t get me wrong, I loathe ooey gooey furniture made by someone who just discovered bent lamination. What I am talking about is the simple visual appeal of a pleasing curve that looks just right. There is some science behind this, or at least math. The shape I use to kick off the conversation around curves, is the catenary curve. You know it well, you just might not be aware of it. A catenary curve is the natural shape a chain takes when held between two points. The Saint Louis Arch is an upside down catenary curve.

Depending on the distance between the points of suspension and the length of the chain, a catenary curve will take many shapes, but it always describes the pull of gravity and the tension caused my resisting it.

When I am designing, I want the shapes to have some relationship to each other and the forces that guide nature. Like a painter using light, I want the curves to flow like I might observe in a river or an electric line. I don’t apply catenary curves as a rule, just a way of describing that curves can have an internal logic and descriptive quality.

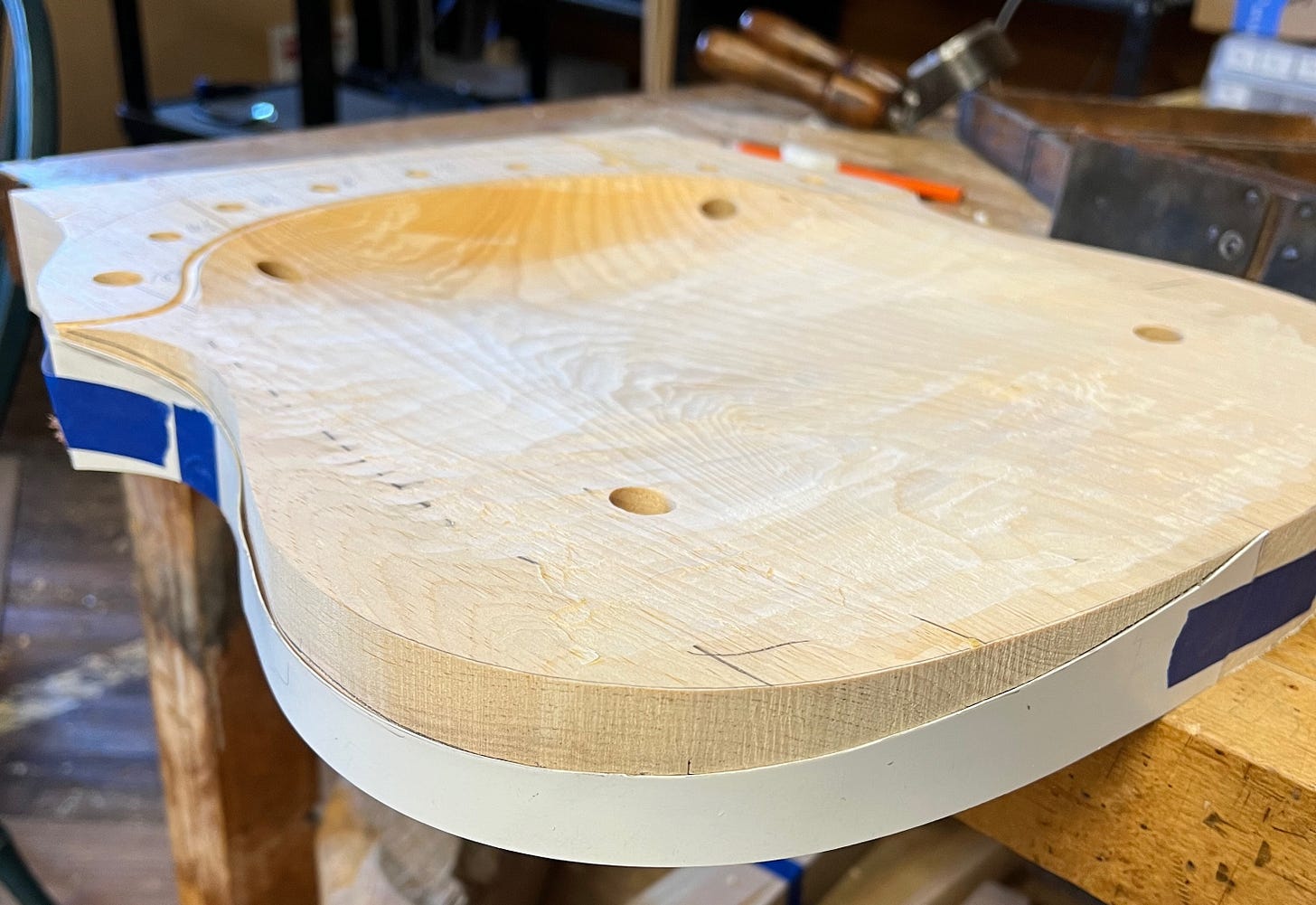

A while back, I made a discovery that surprised me. I used to draw the curve around the front of my seat where the top meets the bottom with a series of lines, as I was taught my David Sawyer and Curtis Buchanan. I show this method in my book. But it’s fussy and a bit tough to teach, so I decided to make a pattern that would wrap around the edge of the seat.

Here is the pattern in place. I made it by drawing a series of lines, but when I flattened out the shape, I was greeted by a single near catenary curve.

I guess it shouldn’t have come as such a big surprise, but the seat has always seemed so complex. I was delighted when I realized that one curve drives the entire shape.

If this shape and line isn’t just right, I feel a sort of agitation. Like the static on a radio station that isn’t quite dialed in, I don’t get relief until it is just right. There are endless opportunities for this kind of attention in chairs. Be it the seat shaping, the leg turning or the spindles, the logic echoes throughout the chair.

Another favorite is the ear of a fan back. It took lots of looking and playing to get the flow of these curves to please my eye. I often think of the curves as having a “speed”, imagining what it would be like to travel them like a road. Abrubt changes can be jarring but a variation in the speed of the curves can guide the eye in a pleasing way.

There are lots of formulas and programs that can be used to arrive at shapes, but I enjoy finding my way by eye. Like any pursuit, the more you engage with it, the more you will develop your skill. Looking at lots of furniture is the best way to get a sense of the power of curves and to develop your own preferences. It’s always revealing to see another chairmaker’s interpretation of a form that I’ve worked with, it’s as though they invited me into their home and offered me their version of a favorite dish.

Your wonder about what is pleasing to us humans is something we both share. I would offer for consideration a short and pithy book by Richard Masland, “We Know It When We See It: what the neurobiology of vision tells us how we think.”

The meta experience of learning how we know what we know is quite illuminating and may assist your search for that elusive, sublime and seductive curve you seek.

A lovely and -- as always -- generative reflection.